A linguist analyzes The $100,000 Pyramid bonus round

I enjoy Pyramid -- the wordplay game show reincarnated over the years and whose latest incarnation is The $100,000 Pyramid. While the regular game play of Pyramid is, frankly, kind of simple (a very loose word guessing game where the only challenge is not to say the clue word or parts of the clue word under time pressure), the bonus round is infinitely interesting, takes real skill, and merits some detailed analysis.

The main game play involves guessing words or terms from an announced theme or topic. However, in the bonus round, played in the Winners' Circle, it's the opposite -- you guess the theme from a list one of the players generates on the fly. Curiously, they never say what it's a list of -- because the answer turns out to be a list of what I would term as head-final noun phrases.

That's a dense and technical term to unpack, which I will do so in the essay to follow. Starting simply: In grade school, I learned a noun was a person, place, or thing (later in this was adjusted to a person, place, animal, or thing). In grad school, I learned what a noun is in technical terms of syntax and logic.

I'll give a taste of that technical analysis here. A sentence in English is comprised of two entities: a noun phrase and a verb phrase. These can be as simple as a single word, as in the simple example I always give -- the shortest verse in the King James Bible, "Jesus wept". "Jesus wept" is certainly a sentence; "Jesus" goes into the noun phrase slot, and "wept" goes into the verb phrase slot. But you can have multiple words going into a slot, so we can replace "Jesus" as in the following and see perfectly acceptable English sentences:

|

The Apostles wept. The Apostles in the hallway wept. The Apostles and their fanboys from Omaha wept. |

A "noun" in this case would be the key component of a noun-phrase, the word on which all the other words depend. This is what syntacticians refer to as the "head" of a "phrasal unit" -- the head of a verb-phrase phrasal unit is a verb, and the head of a noun-phrase phrasal unit is a noun. The example "The Apostles in the hallway" is a noun phrase (however, see below), which has "Apostles" as its noun, the head of the entire noun-phrase phrasal unit.

Regarding the Pyramid bonus round, single-word nouns can be used as clues when giving a list, as in set (1).

|

Eminem turkeys Djakarta radios | (1) |

But so can multi-word noun phrases, as in set (2):

|

Cain's forehead your very dirty floor old-fashioned Japanese women's feet Don Larsen's World Series pitching performance | (2) |

The following examples in set (3) are also multi-word noun phrases, but are not acceptable Pyramid bonus round clues.

|

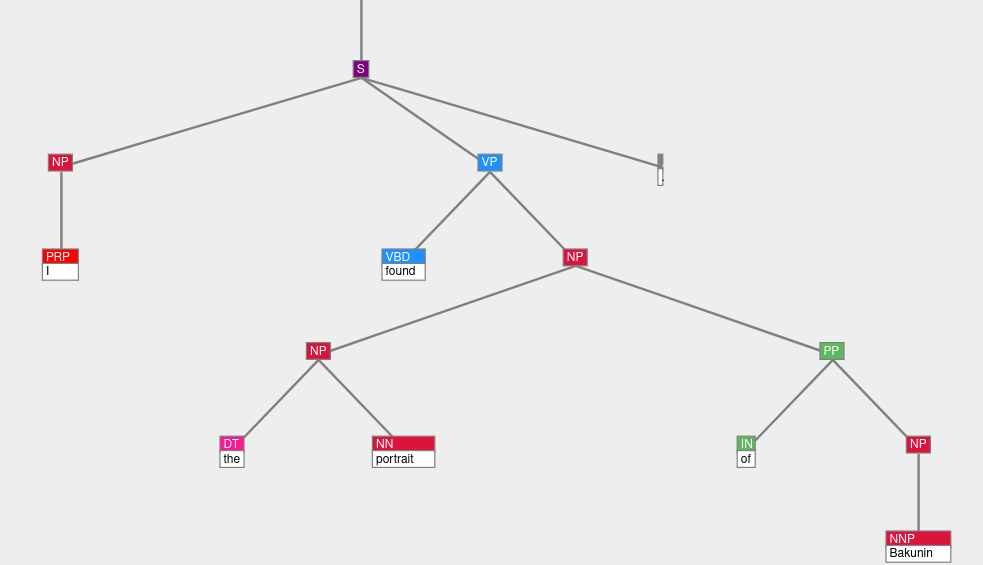

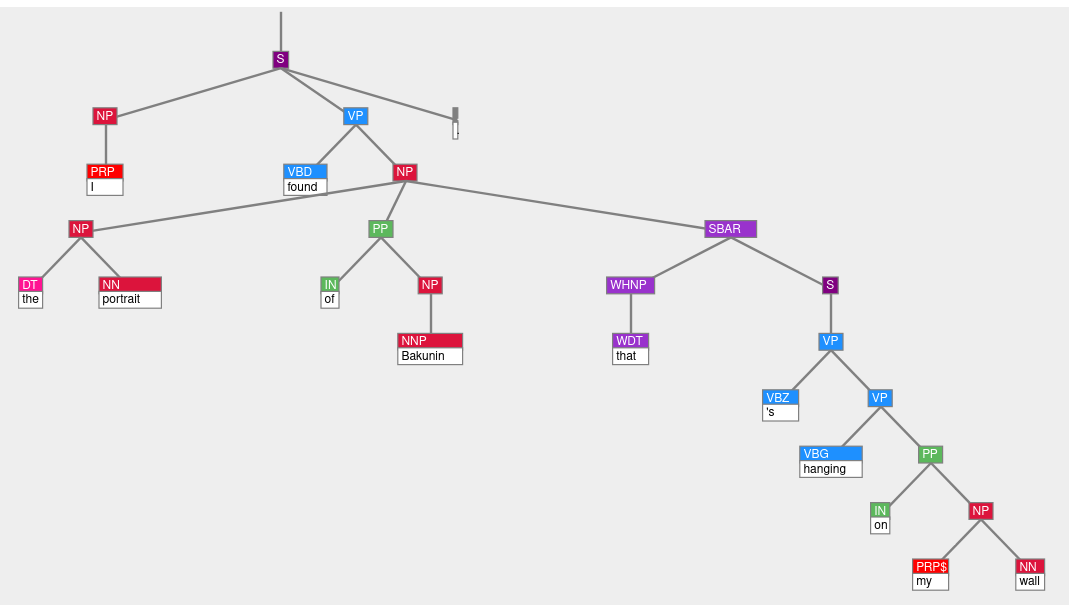

the portrait of Bakunin the portrait of Bakunin that's hanging on my wall | (3) |

If you were to give these as clues in a bonus round, you would be buzzed with a foul for giving an inappropriate clue, or in the current parlance it's "too descriptive". Why is it inappropriate? Because, I posit, they are noun phrases but they are not noun phrases whose head (the key word in the phrase) comes at the end of the phrase -- head-final as I've termed it.

If you review the noun phrases in set (2) above, you'll note that they all end in a noun (forehead, floor, feet, performance) and have no other syntactic constituents (prepositional phrase, relative noun phrase) afterwards.

The examples in set (3) also end with nouns (Bakunin, wall). However, they are preceded by other phrasal constituents (of, that / on). That makes them noun-phrases whose heads are not the last word in the noun phrase -- they're not head-final noun phrases. (The head in both noun phrases is portrait.)

We can see this more clearly when we draw the syntatic trees of the phrases in (3), as part of larger sentences.

Hat tip to James D. McCawley and his excellent book The Syntacic Phenomena of English which was an immensely useful reference in the course of writing this essay.

(Obligatory footnote to syntacticians: Yes, I know that a noun-phrase is, strictly speaking, an expression which "serve[s] as the subject or object of a V but do not have a N as a head" (McCawley 1998, pg. 13), and not the phrasal unit with a N(oun) as its head; that's an N-bar (or N' as it's usually rendered). I'm eliding the full details to some syntactic phenomena in English given the context of this essay -- an exposition of some linguistic analysis of the rules of a televised game show.)

Previous: Remember the protests against the Iraq War

Next: My shoelaces story